ADVERTISEMENT

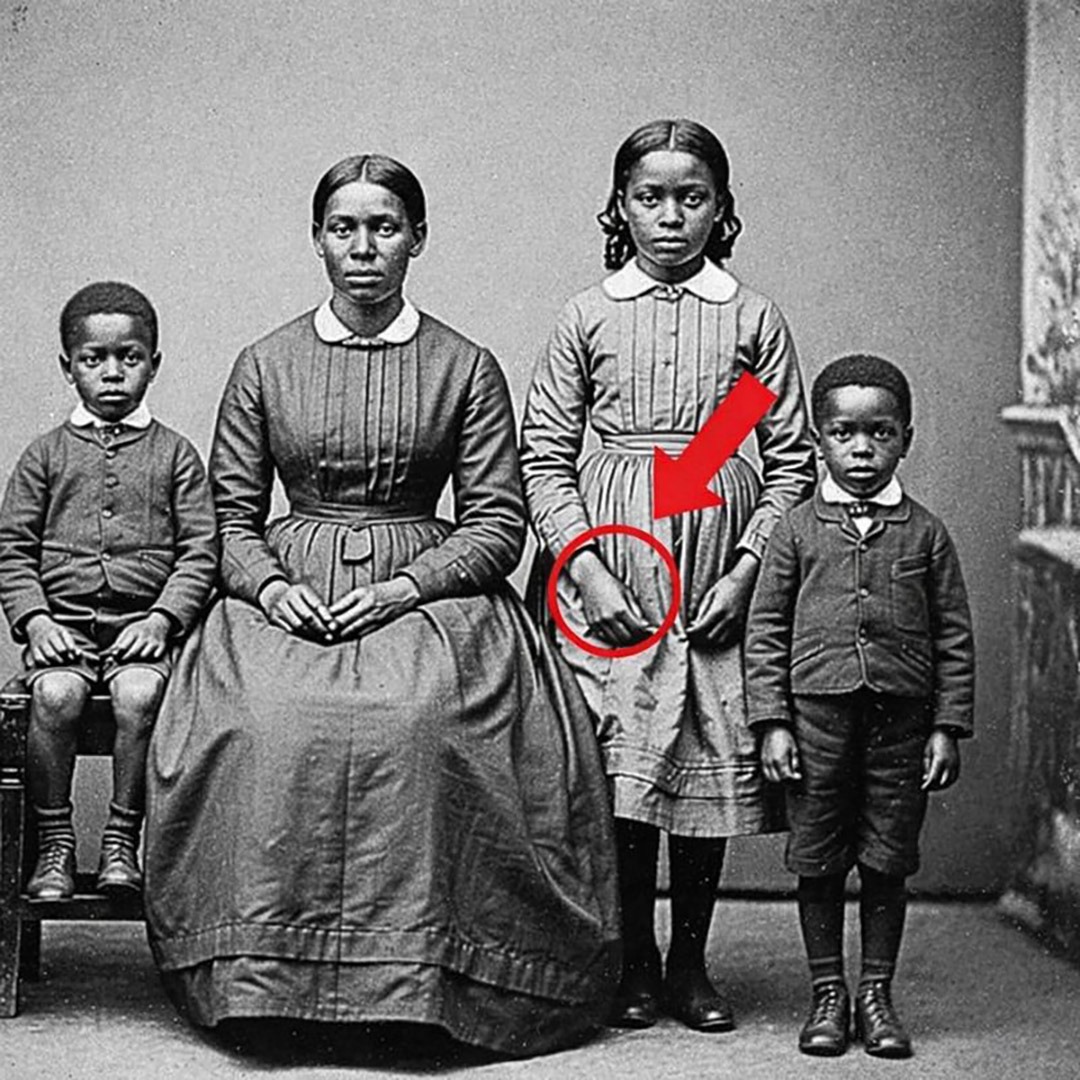

This discovery peeled back the veneer of the portrait’s domestic tranquility. The photograph was no longer just a family record; it was a testament to a life lived in the shadow of bondage, captured at the exact moment that life was attempting to redefine itself in the light of freedom. Driven by a newfound sense of urgency, Sarah began to hunt for the origins of the image. Along the bottom edge of the print, she found a nearly invisible studio stamp. Though faded by over a century of light and dust, two words remained legible: “Moon” and “Free.”

That fragment of information led Sarah to the history of Josiah Henderson, a pioneering African American photographer of the Reconstruction era. Henderson was known among the Black communities of Virginia as a man who documented “The Great Transition.” His studio was a sanctuary where formerly enslaved families went to claim their personhood. In an age where they had been treated as property—nameless, faceless, and disposable—Henderson provided them with something revolutionary: proof of their existence. By sitting for a portrait, these families were asserting that they were no longer objects to be owned, but citizens to be seen.

The historical context of Ruth’s scars painted a grim picture of the era that preceded the photograph. During the years of slavery, children were often subjected to mechanical restraints to prevent them from wandering or attempting to flee from the plantations where they were forced to work. These “quiet” cruelties were a means of control, designed to break the spirit before it had a chance to grow. Ruth had entered the world as a commodity, her body subjected to the literal weight of iron. Yet, here she was in 1872, standing in a photographer’s studio, wearing a clean dress and surrounded by the family that had survived the fire of abolition alongside her.

ADVERTISEMENT