ADVERTISEMENT

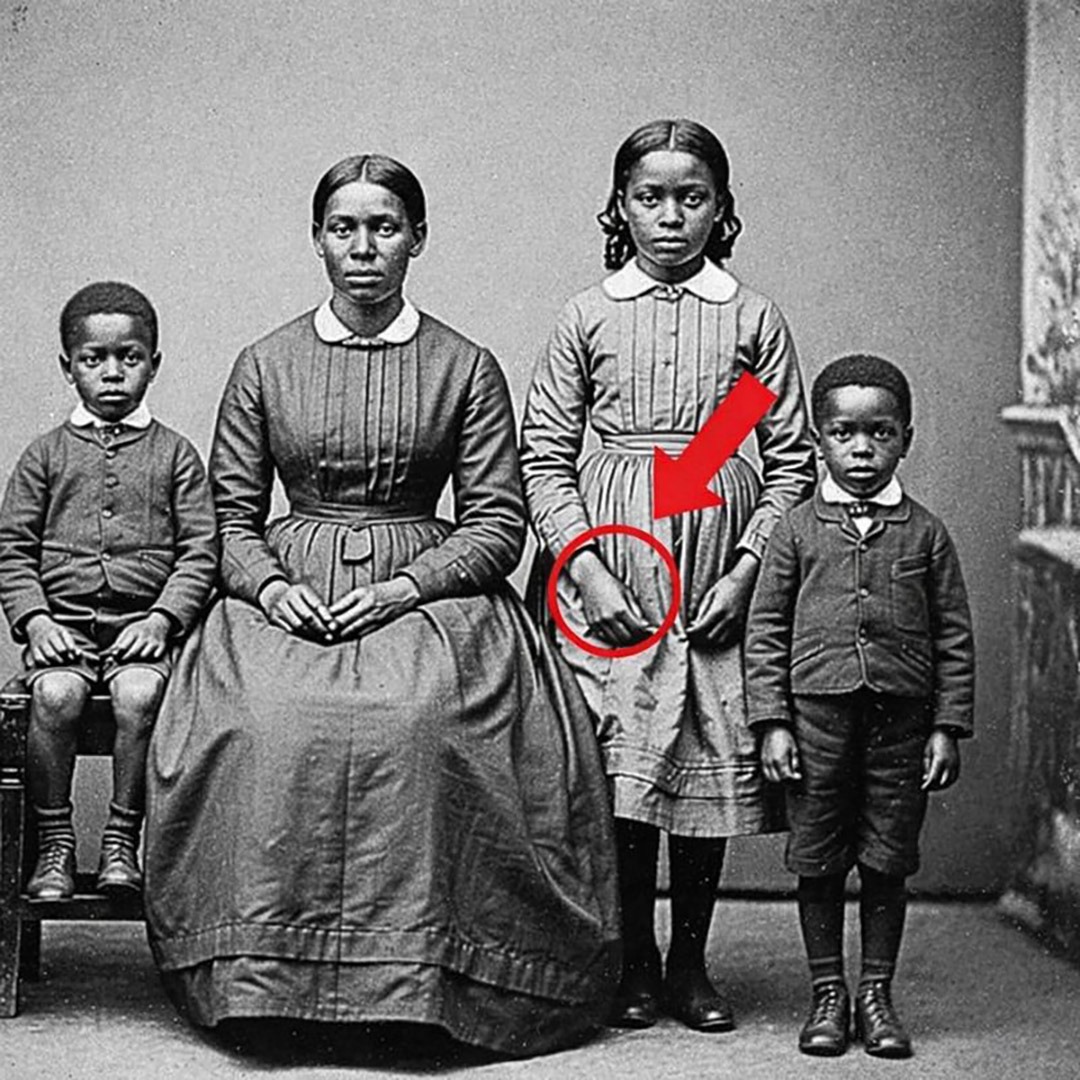

The photograph captures a profound dichotomy. On one hand, it shows the success of the Washington family’s transition. James and Mary had achieved what was once a legal impossibility: a stable, autonomous household. Records showed that their children were enrolled in school, learning to read and write—acts that had been punishable by death just a decade prior. On the other hand, the photograph refused to let the past go. Ruth’s wrist was a bridge between two worlds: the world of the shackle and the world of the pen.

Decades after the photograph was taken, a descendant of the Washington family uncovered a handwritten note in the margins of a family Bible that had been passed down through generations. The note, attributed to one of James’s sons, read: “My father wanted us all in the picture. He said the image would outlast our voices.” James Washington understood that while their physical bodies would eventually fail and their personal stories might be forgotten by the wider world, the photograph would remain as an objective witness to their dignity. He knew that for a people who had been systematically erased from history, the visual record was a form of resistance.

ADVERTISEMENT