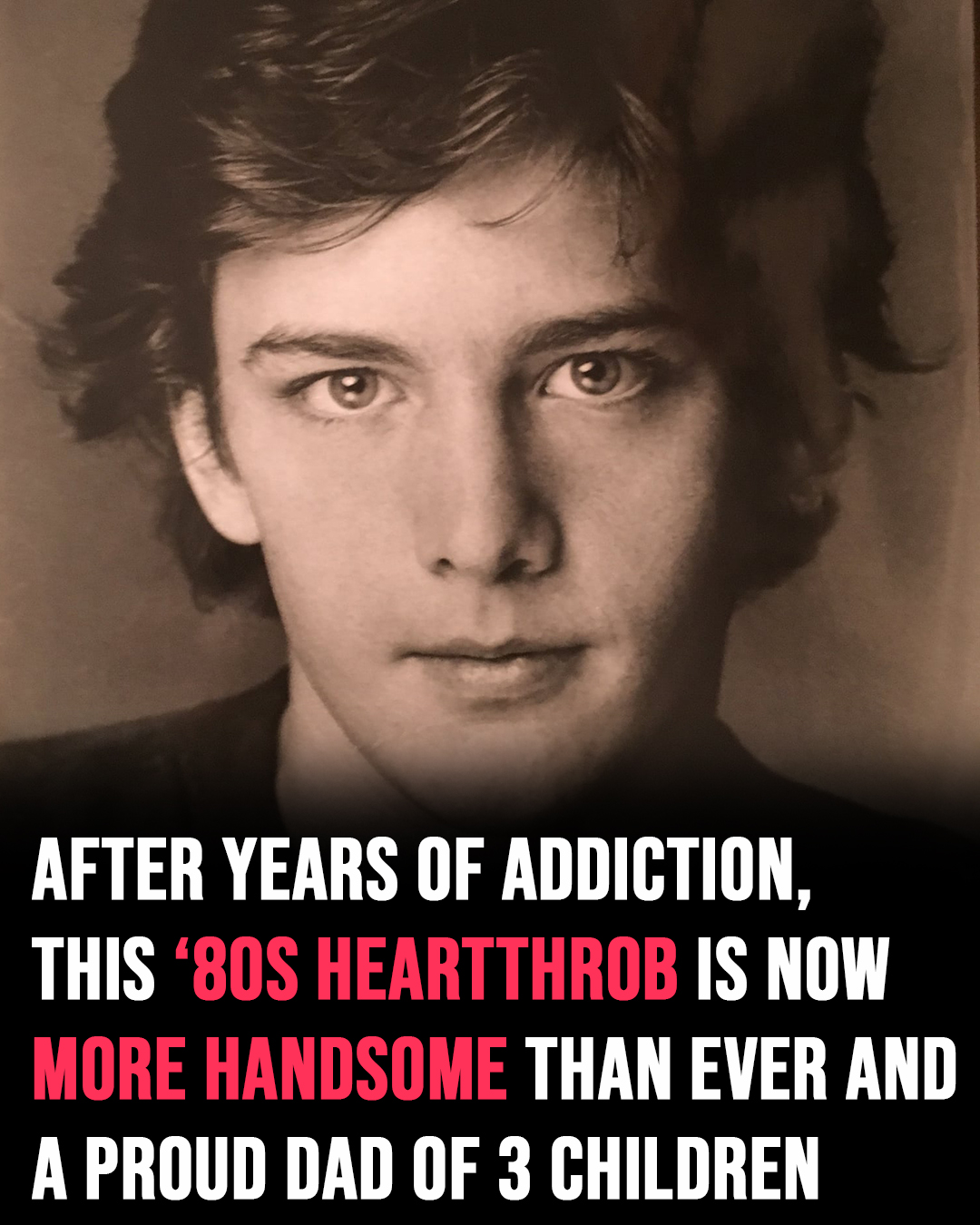

For millions of moviegoers in the 1980s, Andrew McCarthy was more than a Hollywood heartthrob. He was the face of quiet longing, the soft-spoken counterweight to louder leading men, the kind of presence that made teenage crushes feel personal and strangely intimate. His image was taped to bedroom walls, tucked into notebooks, and burned into pop culture through films that defined a generation. Yet behind the camera-ready smile and carefully lit close-ups, his real life was far more turbulent—and far more compelling—than any role he ever played.

Born in 1962 in Westfield, New Jersey, McCarthy grew up far removed from red carpets and studio backlots. He was raised in a middle-class household, the third of four boys, with no family ties to the entertainment industry and no clear roadmap to fame. His childhood was outwardly ordinary, but internally marked by isolation. As a teenager, he felt like an observer rather than a participant, a feeling that would later shape both his acting style and his struggles.

Drawn to performance as a way to belong, he enrolled at New York University to study acting. It was supposed to be the first step toward something bigger. Instead, it nearly ended his ambitions altogether. He skipped classes, drifted, and was eventually expelled after two years. For most people, that would have been the end of the story. For McCarthy, it was the moment everything changed.

Just weeks later, he answered an open casting call for a film called Class. Surrounded by hundreds of hopefuls, he assumed nothing would come of it. Instead, he was cast opposite Jacqueline Bisset in a provocative role that instantly put him on Hollywood’s radar. One week he was a failed college student; the next, he was a working actor with industry attention. When NYU offered to let him return and count the film as independent study, he declined. He was already moving forward.

The mid-1980s turned him into a cultural phenomenon. Films like St. Elmo’s Fire, Pretty in Pink, Mannequin, and Weekend at Bernie’s cemented his status as a defining figure of the era. He was grouped with the so-called Brat Pack, a label that came with fame, scrutiny, and a narrative he never quite fit. While others leaned into excess, McCarthy recoiled from attention. He was introverted, anxious, and deeply uncomfortable with celebrity culture, even as it elevated him.

That discomfort found an outlet in alcohol.

What began as social drinking escalated as fame intensified. Alcohol became a tool—liquid confidence that quieted his fears and gave him a temporary sense of control. On screen, he was praised for sensitivity and emotional depth. Off screen, he was often hungover, disconnected, and unraveling. He later admitted that during some of his most beloved performances, he was barely holding himself together, physically and emotionally.

Substances offered escape, but at a cost. While he avoided heavy drug use on set, he didn’t escape addiction. Fame amplified access and isolation in equal measure, creating the perfect conditions for self-destruction. By the late 1980s, the pressure and internal conflict became impossible to ignore.

In 1989, just before filming Weekend at Bernie’s, McCarthy stopped drinking abruptly and withdrew from the social scene. For someone already comfortable with solitude, isolation wasn’t the hardest part. Staying sober was. A relapse during a later project triggered several years of decline, culminating in a physical and emotional collapse that forced him to confront reality. At 29, he entered rehab and committed fully to recovery.

That decision marked the true turning point of his life.

Sobriety didn’t just save him—it redirected him. As Hollywood’s obsession with youth shifted elsewhere, McCarthy quietly reinvented himself. He moved behind the camera, directing episodes of major television series and discovering a sense of authorship he’d never felt as an actor-for-hire. His work expanded into prestige television, where his sensitivity translated into strong storytelling instincts.

Then came an unexpected second act: writing.

McCarthy found a new voice as a travel writer, earning recognition for deeply personal, reflective essays published in outlets like National Geographic Traveler and Men’s Journal. In 2010, he was named Travel Journalist of the Year, a title that surprised many but made perfect sense to him. Acting and writing, he explained, were simply different forms of storytelling. Both required presence, vulnerability, and honesty.

Travel, in particular, stripped away the noise. Away from expectations and identity, he found clarity. It sharpened his awareness, grounded him, and brought out the best version of himself—an experience many readers connected with in an era obsessed with reinvention, mental health awareness, and authentic living.

His personal life evolved alongside his professional transformation. He married his college sweetheart years after reconnecting, became a father, divorced, and later remarried Irish writer and director Dolores Rice. Together they built a family and a life far removed from Hollywood spectacle. Today, he lives quietly in New York, raising children, directing television, and writing with intention.

Decades after his Brat Pack peak, fans still respond to him with affection and nostalgia. Social media comments praise how well he’s aged, how timeless his appeal remains. But McCarthy himself resists romanticizing the past. He acknowledges the impact of those films without clinging to them. The admiration belongs to the audience’s memories, not his present identity.

What makes Andrew McCarthy’s story resonate today is not his rise to fame, but his refusal to be defined by it. In an industry known for burnout, addiction, and early exits, he chose growth over collapse. He survived the machine, stepped away from the noise, and built a second life rooted in sobriety, creativity, and family.

In a culture fascinated by celebrity comebacks, mental health journeys, and second acts, his real-life narrative stands as proof that success doesn’t have to be loud to be meaningful. Sometimes the most powerful story isn’t the one that makes you famous—it’s the one that teaches you how to live afterward.

Andrew McCarthy didn’t just outgrow Hollywood. He rewrote the script entirely, and in doing so, created a legacy far richer than any role he ever played pasted