ADVERTISEMENT

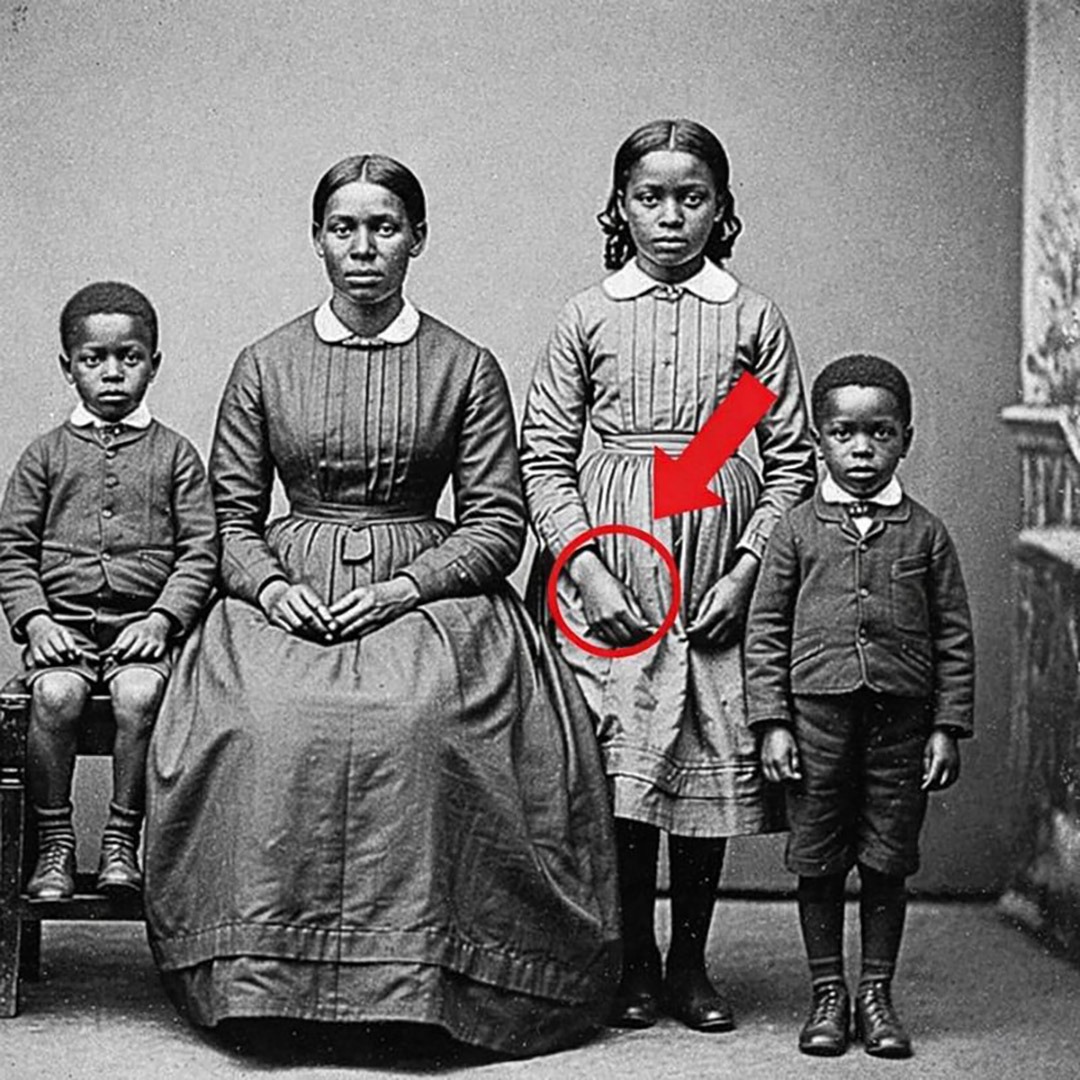

With the photographer identified, the genealogical threads began to knit together. Through a painstaking search of Richmond census records, church ledgers, and property deeds from the 1870s, the family finally stepped out of the fog of anonymity. Their surname was Washington. The father, James, had established himself as a laborer in the city, working grueling hours to provide for his wife, Mary, and their five children. The young girl with the marked wrists was named Ruth.

The historical context of Ruth’s scars painted a grim picture of the era that preceded the photograph. During the years of slavery, children were often subjected to mechanical restraints to prevent them from wandering or attempting to flee from the plantations where they were forced to work. These “quiet” cruelties were a means of control, designed to break the spirit before it had a chance to grow. Ruth had entered the world as a commodity, her body subjected to the literal weight of iron. Yet, here she was in 1872, standing in a photographer’s studio, wearing a clean dress and surrounded by the family that had survived the fire of abolition alongside her.

Decades after the photograph was taken, a descendant of the Washington family uncovered a handwritten note in the margins of a family Bible that had been passed down through generations. The note, attributed to one of James’s sons, read: “My father wanted us all in the picture. He said the image would outlast our voices.” James Washington understood that while their physical bodies would eventually fail and their personal stories might be forgotten by the wider world, the photograph would remain as an objective witness to their dignity. He knew that for a people who had been systematically erased from history, the visual record was a form of resistance.

Today, the portrait of the Washington family is no longer tucked away in a dark drawer or a digital folder. It has become a centerpiece of an exhibition dedicated to the resilience of Black families during the Reconstruction. When visitors look at the image, they are often drawn first to the father’s protective hand on his son’s shoulder or the mother’s proud, weary eyes. But inevitably, their gaze settles on Ruth’s wrist.

ADVERTISEMENT