ADVERTISEMENT

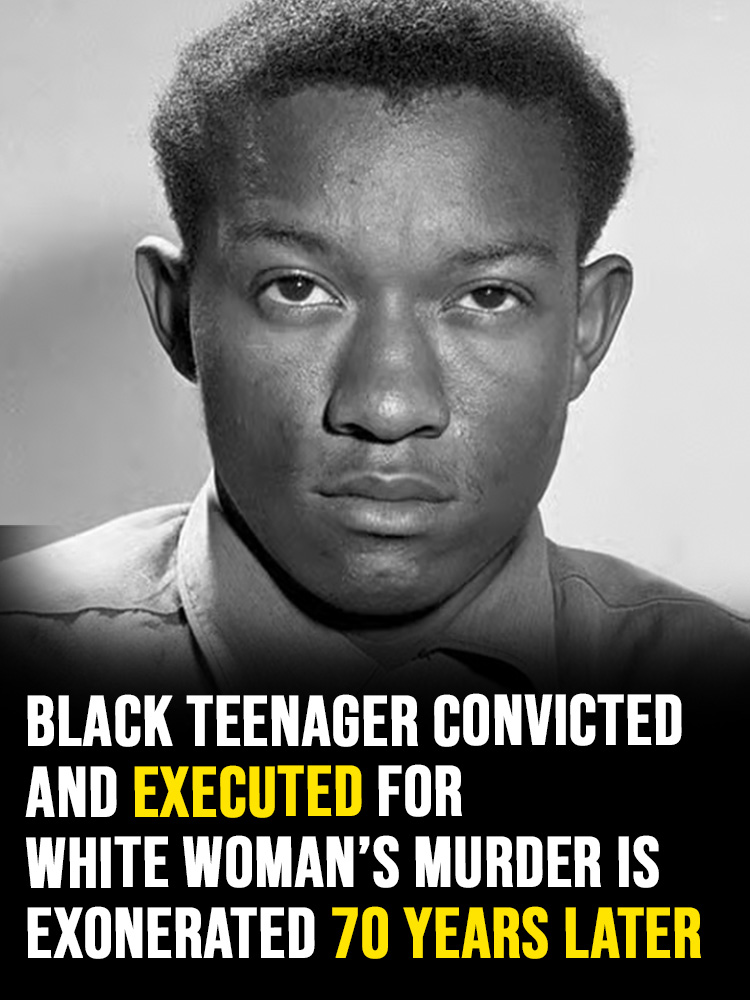

Walker’s arrest was fundamentally flawed from the start. He possessed an airtight alibi: on the night of the murder, he was at the hospital attending the birth of his first and only child. More than ten eyewitnesses were prepared to testify that he was nowhere near the scene of the crime. Despite this, Walker was subjected to hours of relentless interrogation. He was stripped down emotionally and physically, threatened with the electric chair, and denied basic protections. Exhausted and terrified, he was eventually coerced into signing a confession.

During the trial, the prosecution’s case rested almost entirely on this forced statement. There was no forensic evidence linking Walker to Venice Parker, no DNA—which did not exist as a legal tool at the time—and no circumstantial evidence that placed him at the bus stop. Even the two witnesses who claimed to have seen him in the general area that night admitted they had not witnessed any struggle or crime. Walker took the stand in his own defense, recanting the confession and describing the duress under which it was obtained. He told the court, “I feel that I have been tricked out of my life.”

The path to exoneration was paved by the relentless work of the Innocence Project and the Dallas County District Attorney’s office under John Creuzot. By re-examining appellate court decisions and historical records, investigators were able to highlight the systemic failures that led to Walker’s execution. The modern review made it clear that the evidence against him was non-existent and the confession was a product of coercion.

The most poignant moment of this seventy-year journey occurred during the adoption of the exoneration resolution. In a room filled with the heavy weight of history, two men met for the first time: Edward Smith, the son of the man wrongfully executed, and Joseph Parker, the son of the woman whose murder started it all. In an act of profound grace and moral clarity, Joseph Parker stood beside Edward and affirmed what the evidence now makes undeniable: Tommy Lee Walker was an innocent man.

District Attorney John Creuzot released photos of the meeting, capturing a moment that transcended generations of racial tension and personal grief. “Justice does not expire with time,” Creuzot stated, emphasizing that the state has a moral obligation to correct its errors, no matter how much time has passed or how many of the original participants are gone. The resolution adopted by the Commissioners Court officially acknowledged the “irreparable harm” caused to Walker, his family, and the broader community.

ADVERTISEMENT