ADVERTISEMENT

The late 1960s provided the perfect Petri dish for Manson’s particular brand of sociopathy. It was an era defined by a collective searching—a generation of young people who had rejected the rigid structures of their parents’ lives but had not yet found a new foundation. Into this vacuum stepped Manson, a man who spoke the language of the revolution but harbored the heart of a tyrant. To the lost, the lonely, and the searching, he offered more than just a philosophy; he offered a sense of belonging. He understood that the greatest human hunger is to be seen and accepted, and he used that hunger to build a “Family” of followers who were essentially mirrors, reflecting his darkest fantasies back at him with religious fervor.

Manson’s genius lay in his ability to wrap extreme violence in the soft language of peace and communal love. He took the ideals of the Haight-Ashbury scene—freedom, shared living, and spiritual enlightenment—and twisted them into a psychological prison. He didn’t just lead his followers; he consumed their identities. He broke them down through isolation, sleep deprivation, and the strategic use of hallucinogens until their will was entirely subsumed by his own. The murders that eventually shocked the world—the brutal slaughter at the Tate and LaBianca residences—were not sudden, erratic eruptions of evil. They were the logical, inevitable endpoint of a life that had been warped from its very inception. They were the final act of a man who believed that if he could not be a part of the world, he would burn it down so that he could reign over the ashes.

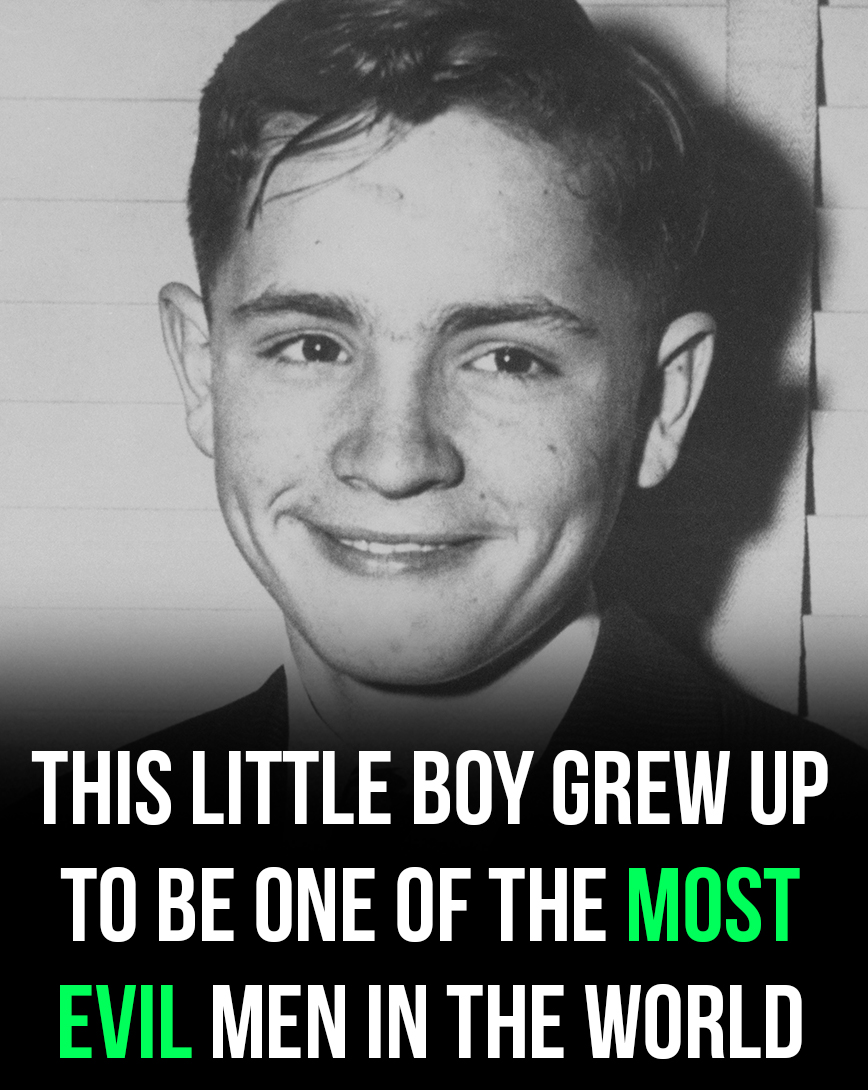

When we look at the harmless-looking boy in the old black-and-white photographs, we are forced to ask a question that haunts our modern social fabric: how many future monsters are we quietly creating right now, in plain sight? We live in a world where children still fall through the cracks of overburdened systems, where neglect is still a quiet epidemic, and where the internet has provided new, digital “alleys” for the lost to find the wrong kind of belonging. The radicalization of the young and the vulnerable by charismatic, predatory figures is not a phenomenon that died in 1969; it has merely moved into new arenas.

The story of Charles Manson is a cautionary tale about the high cost of indifference. It reminds us that when we fail to provide a stable, loving foundation for a child, we create a void that will eventually be filled by something else—and that “something” is rarely benign. It teaches us that the masks of charm and spiritualism can hide a bottomless well of resentment. Most importantly, it reminds us that evil is rarely a bolt from the blue. It is a slow-growing vine, nurtured by the very institutions meant to prune it, until it eventually chokes the life out of everything it touches.

As we reflect on the carnage associated with the Manson name, we must look beyond the spectacle and into the source. The boy in the photograph was once just a child who needed a home, a name, and a reason to believe in the goodness of others. Because he found none of those things, the world eventually had to reckon with the man he became. The tragedy of Charles Manson is not just what he did to his victims, but what a broken world did to the boy he used to be, and the terrifying reality that the same machinery of neglect is still in operation today.