ADVERTISEMENT

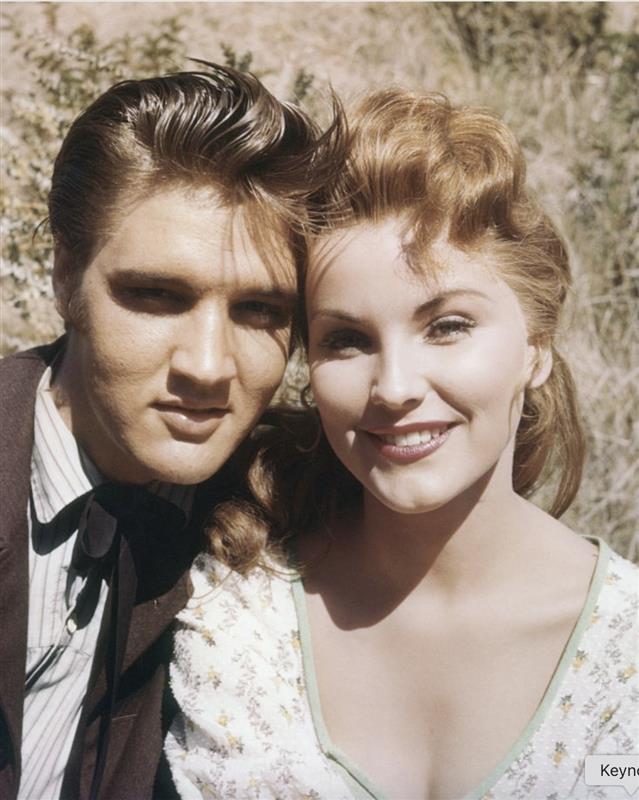

A big part of the film’s charm comes from the people around him, especially Debra Paget, who played Cathy. Paget was a rising Hollywood name, and by some accounts she arrived on set with skepticism. She’d heard plenty about this “new singing sensation,” and not all of it flattering. Then she met him. Elvis, by most recollections, disarmed people the old-fashioned way: good manners, quiet confidence, and an almost formal respect—especially toward her mother. Their on-screen chemistry carries the romance even when the script leans a little broad.

The off-screen story around Paget has taken on a life of its own over the decades. Rumors persisted that Elvis was taken with her enough to consider proposing, and that she declined, reportedly drawn instead to Howard Hughes. What’s more concrete is that Paget’s look in the film—particularly her hair—made an impression that echoed later. Years afterward, Priscilla Presley would be influenced by Paget’s style, a small thread connecting Elvis’s early Hollywood life to the world he eventually built around himself.

The title song, “Love Me Tender,” has its own layered history. It’s adapted from “Aura Lee,” a ballad associated with the Civil War era, then reshaped into something softer and more romantic. Elvis performed it on The Ed Sullivan Show before the film’s release, and the public response was immediate and massive. The song didn’t just sell tickets—it became part of his identity, the kind of track people could hum without even knowing where they first heard it.

Then there’s the odd detail that fans still point out: the hair.

Originally, Clint Reno dies in the film—a bold ending, especially for a debut movie starring a rapidly rising idol. But the story goes that Elvis’s mother, Gladys, was deeply upset by the idea of audiences watching her son die on screen. The production softened the blow by adding a final moment: Elvis’s silhouette singing “Love Me Tender” over the closing credits. It’s meant to comfort the audience, to send them out with music instead of shock.

In doing so, it created a weird continuity hiccup. In the closing silhouette, Elvis’s hair appears noticeably darker—dyed black—compared to earlier scenes where it reads closer to his natural shade. It’s not a plot-breaking flaw, but it’s the kind of detail that becomes irresistible once you notice it, like the movie briefly revealing the machinery behind the magic.

Love Me Tender is also sprinkled with the kind of old-Hollywood goofs that make vintage films feel human. A zipper appears where it shouldn’t. A modern car reportedly sneaks into a shot. A guitar keeps “playing” after Elvis stops strumming. A gun disappears and reappears depending on the angle. None of it ruins the experience. If anything, it adds to the sense that you’re watching a real artifact: a studio rushing to capture a phenomenon, patched together with practical decisions, imperfect takes, and the confidence that the star would carry it anyway.

Critics have never crowned Love Me Tender as Presley’s greatest film, and it’s not hard to see why. The story is straightforward, sometimes melodramatic, and very aware of its mission to showcase Elvis. But as a piece of pop history, it’s hard to beat. It’s the moment the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll becomes a Hollywood leading man, the moment the screaming crowds follow him from the stage to the screen, and the moment you can still see the boy behind the legend trying to prove he belongs there.

Watch it now and you’re not just watching a movie. You’re watching a turning point—an industry, a culture, and a young man stepping into a new arena, learning in real time how to carry the weight of a name the world had already decided would last forever.