The tradition of the gold star is rooted in the fertile soil of American resilience during the First World War. In 1917, as the nation mobilized for a conflict of unprecedented scale, families across the country searched for a visual language to express both their pride and their anxiety for loved ones serving overseas. Army Captain Robert L. Queisser is credited with creating the first Blue Star Service Banner, a simple white flag with a red border featuring a blue star for each of his sons on active duty. The banner became a national phenomenon, appearing in the windows of homes, storefronts, and places of worship. It was a way for a mother or a wife to say, “A part of my heart is currently in harm’s way.”

However, as the casualty lists began to grow, the blue star underwent a heartbreaking transformation. When a service member was killed in action or died from wounds sustained in the conflict, the blue star was covered with a gold one. This simple change in color represented a profound shift in the family’s reality; hope was replaced by mourning, and the pride of service was tempered by the permanence of loss. The gold star became a shorthand for a sacrifice that words were often insufficient to describe. It allowed a community to identify those among them who were carrying the heaviest of burdens, facilitating a silent network of support and shared gratitude.

National recognition of this symbol followed quickly. In 1918, President Woodrow Wilson authorized a suggestion from the Women’s Committee of the Council of National Defense: that mothers who had lost children in the war wear a black armband adorned with a gold star. This official endorsement cemented the gold star as the definitive emblem of military sacrifice in the American consciousness. In the years following the Great War, the bond between these grieving families led to the 1928 formation of American Gold Star Mothers, Inc. The organization provided a sanctuary for those navigating a specific type of grief that few outside the military community could fully comprehend. They became a powerful force for advocacy and remembrance, ensuring that the names of the fallen were not whispered in the shadows but honored in the light of day.

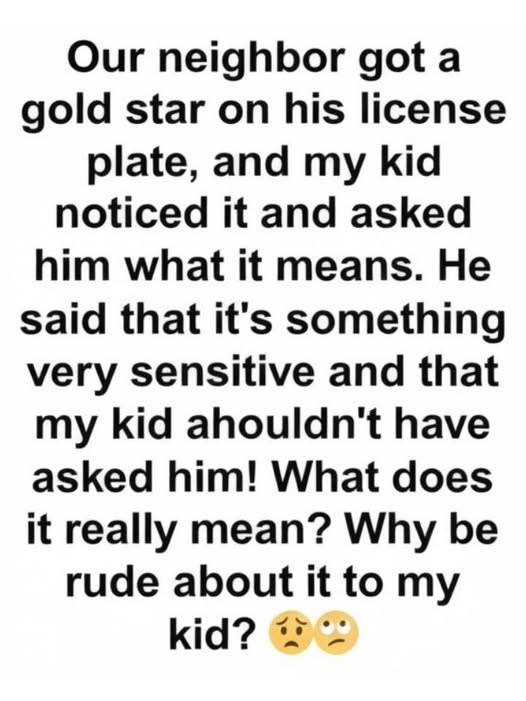

In 1936, the significance of these families was further codified when Congress designated the last Sunday of September as Gold Star Mother’s Day. Over time, this recognition expanded to include all Gold Star families, acknowledging that the ripple effects of a service member’s death extend to fathers, siblings, spouses, and children. Today, many states offer specialized gold star license plates to eligible family members, allowing this historic symbol of sacrifice to move through the modern world.

These license plates serve a unique purpose in our contemporary society. In an era where military service is often concentrated within a small percentage of the population, the gold star acts as a bridge between the civilian and the soldier. It serves as a reminder that the “fallen” are not just statistics in a news cycle or names on a granite wall; they were sons who loved to fix old cars, daughters who were brilliant at mathematics, and parents who hoped to see their children graduate. The person driving the car with the gold star plate carries the memory of that person into the world every day. For the driver, the plate is often a way to keep the memory of their loved one active—to ensure that even in the most mundane moments, like waiting at a red light or sitting in a grocery store parking lot, their relative’s sacrifice remains visible.