The legend of Judy Garland is often draped in the shimmering fabric of the “Golden Age” of Hollywood, a time of technicolor dreams and ruby slippers.1 Yet, beneath the sequins and the celestial voice that could command an entire auditorium into silence, lay a foundation of profound instability and systemic cruelty. To understand Judy Garland is to understand the machinery of a studio system that viewed human beings as assets to be managed, polished, and ultimately discarded once their shine began to fade. Her life was not merely a series of performances; it was a battle for autonomy that began almost from the moment of her birth in Grand Rapids, Minnesota, as Frances Ethel Gumm.

Long before she was a household name, she was a child wandering into a storm she never asked to navigate. Born to vaudeville performers, she was pushed onto the stage before she had even reached her third birthday. While other children were learning the basics of social interaction, she was learning how to hold a note and read a crowd. Her home life offered no sanctuary from the pressures of performance. Her parents’ marriage was a volatile cycle of separations and reconciliations, fueled in part by the scandalous rumors surrounding her father’s personal life. The family’s move to Lancaster, California, in 1926 was less a pursuit of the American dream and more a desperate flight from the whispers and judgments of their small-town neighbors. In this environment of secrecy and emotional upheaval, the stage became the only place where the young girl felt a semblance of security or affection. As she would later reflect with heartbreaking clarity, the only time she felt truly “wanted” was when she was under the spotlight.

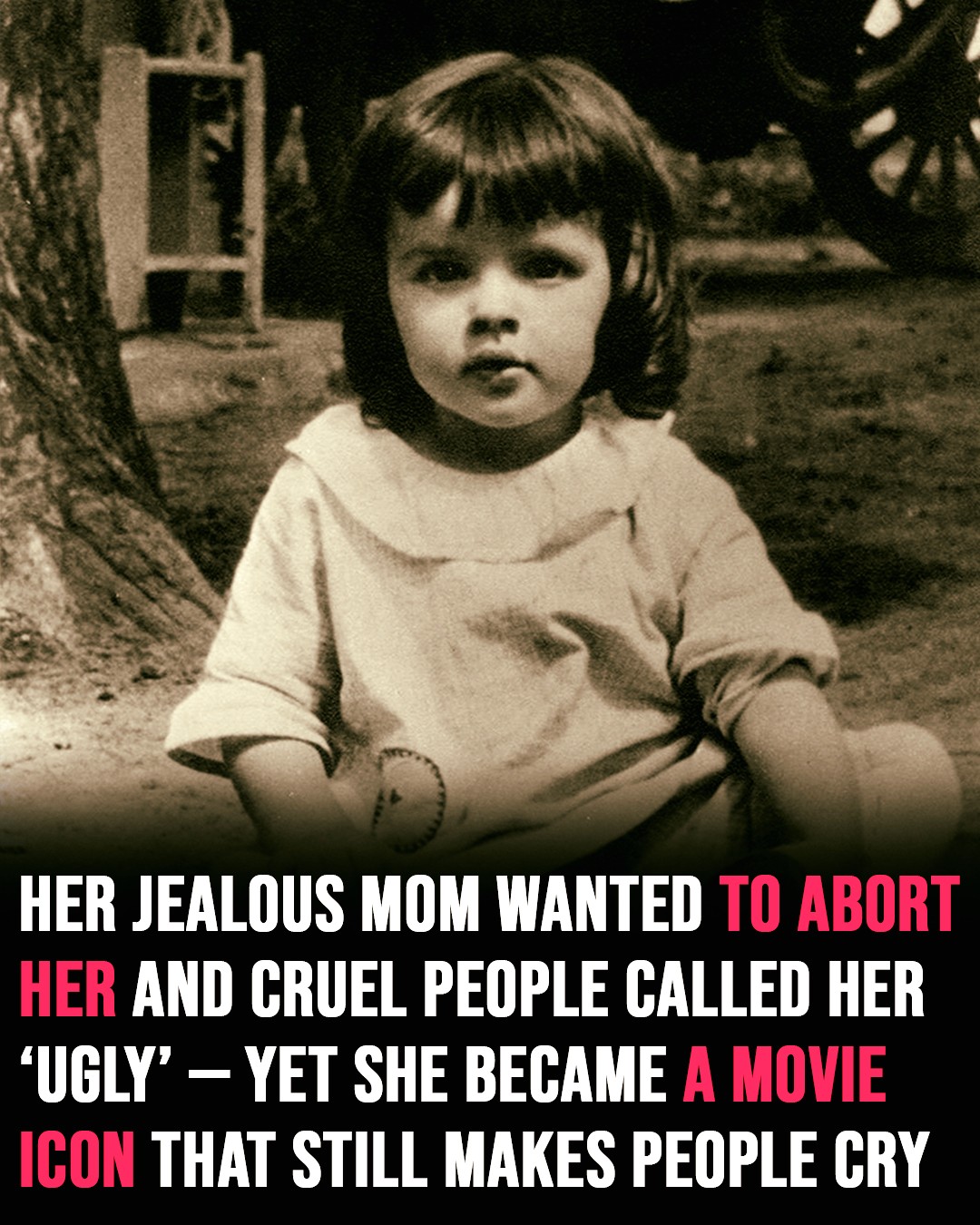

The tragedy of Garland’s childhood was exacerbated by the woman who should have been her greatest protector: her mother, Ethel Gumm. Described by Garland in later years as the “real Wicked Witch of the West,” Ethel was the quintessential stage mother, driven by a relentless ambition that left no room for her daughter’s well-being. The stories that emerged from this period are harrowing. Ethel reportedly used threats of physical violence to ensure the young girl performed, famously telling her that she would break her “off short” if she didn’t get out and sing. More devastatingly, Garland would later claim that her mother had attempted to terminate the pregnancy while carrying her, a fact she recounted with a dark, defensive humor, joking that her mother must have rolled down nineteen thousand flights of stairs to achieve the task. This sense of being an unwanted burden followed her into her professional life, where she was traded from the control of an abusive mother to the control of an indifferent studio.

When Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) signed her in 1935, the exploitation moved from the domestic sphere to the corporate one. The studio, led by the formidable Louis B. Mayer, immediately began to dismantle her self-esteem to ensure she remained compliant. Despite her obvious beauty and world-class talent, she was labeled the “ugly duckling” of the lot. Surrounded by more conventional “glamour girls” like Lana Turner and Elizabeth Taylor, Garland was made to feel physically inferior. Mayer himself allegedly referred to her as his “little hunchback.”2 To keep her productive and thin, the studio implemented a regime that would be considered criminal today. She was placed on a diet of black coffee, chicken soup, and a constant rotation of pills. Amphetamines were administered to keep her awake through grueling eighteen-hour workdays, and barbiturates were given to force her into sleep so she could repeat the cycle the following morning. This chemical leash created a dependency that would haunt her until her final breath.

The year 1939 served as the ultimate turning point, as “The Wizard of Oz” catapulted her into the stratosphere of global fame. As Dorothy Gale, she became the symbol of innocence and hope for a generation reeling from the Great Depression and facing the brink of war. Yet, the irony of her performance was that while she sang of a land “somewhere over the rainbow” where troubles melt like lemon drops, her own life was becoming increasingly fractured. During the production, she was still being subjected to strict caloric restrictions and chemical stimulants. The loss of her father to spinal meningitis during her early years at MGM had already left a void in her heart, and the studio’s refusal to allow her adequate time to grieve only deepened her reliance on the pills that numbed her reality.

Throughout the 1940s and 50s, Garland delivered some of the most iconic performances in cinematic history. From the nostalgic charm of “Meet Me in St. Louis” to the sophisticated brilliance of “Easter Parade,” she proved herself to be a versatile and unmatched entertainer. Her partnership with Mickey Rooney became a staple of American cinema, but behind the “let’s put on a show” enthusiasm was a woman spiraling into exhaustion. By the time she filmed “A Star Is Born” in 1954, the parallels between her life and the tragic narrative of the film were impossible to ignore. She played Vicki Lester, a rising star, but she deeply identified with the character of Norman Maine—a brilliant artist destroyed by the very industry that once celebrated him.

As she entered her thirties and forties, the industry that had raised her began to turn its back on her. Her “difficult” reputation—largely a byproduct of the health issues and addictions the studio had caused—led to her being fired from projects and labeled a liability. Yet, Garland possessed a resilient spirit. She transitioned into a legendary concert performer, breaking records at the Palace Theatre and the Hollywood Bowl. She often joked about her constant “comebacks,” famously stating that she was getting tired of having to come back so often. It was a line that masked a profound weariness. She had been working for forty years by the time most people were reaching the midpoint of their careers.

The end of her story came far too soon. On June 22, 1969, at the age of 47, Judy Garland was found dead in her London home.3 The cause was an accidental overdose of barbiturates—the very substances she had been introduced to as a child to keep the MGM assembly line moving. Her death was not a sudden shock to those who knew her, but rather the quiet conclusion to a life that had been under immense pressure for too long. She had survived numerous suicide attempts and financial ruins, always bolstered by the love of her children—Liza, Lorna, and Joey—and the unwavering devotion of her fans.

Ultimately, the story of Judy Garland is not just a tragedy; it is a testament to the endurance of the human voice. Despite the trauma of her childhood, the cruelty of the studio system, and the demons of addiction, she remained one of the most gifted communicators to ever grace the screen. Her daughter Lorna Luft once wisely noted that having tragedies in one’s life does not necessarily make a person a tragic figure. Garland was a woman of immense wit, warmth, and courage.4 She was a victim of a specific era of Hollywood, but she was also a victor who managed to leave behind a legacy of beauty that continues to provide comfort to millions. When we hear her sing today, we aren’t just hearing a professional vocalist; we are hearing the soul of a woman who, despite everything, never stopped searching for her own way home.